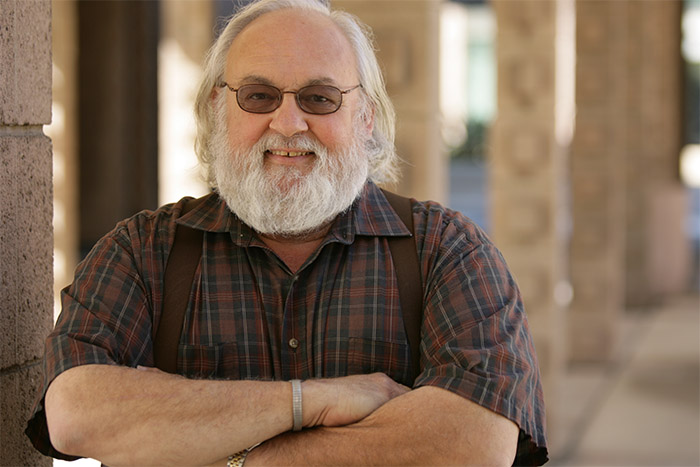

“Remembering Richard G. Olson, Professor Emeritus of History,” by the HSA department faculty

December 8, 2020

The members of the Harvey Mudd Department of Humanities, Social Sciences, and the Arts (HSA) are deeply saddened by the loss of our colleague Richard G. (Dick) Olson, who died in June, a few months shy of what would have been his 80th birthday. Though he retired from the College in 2011, Dick remained closely connected to the department and his departmental colleagues and continued to be a vibrant, visible presence on campus. He was often in his emeritus faculty office in Sprague, eager as ever for conversation with whoever might happen by, and usually at work on new writing at a time in his career when nobody would have faulted him for slowing down.

Dick’s contributions to the HSA department and to the College were profound. After graduating from the College in 1962 and receiving his PhD in history from Harvard University in 1967, Dick returned to Harvey Mudd in 1976 as professor of history, having previously reached the rank of associate professor of history with tenure at the University of California at Santa Cruz. (A fuller recounting of Dick’s life and achievements.)

From the time of his arrival, Dick brought with him a commitment to embodying the College’s mission in his teaching and to deploying his considerable wisdom and vision in leadership roles at the College. In his 35 years as an active faculty member, he served as HSA department chair, chair of the faculty, and freshman division director, and offered some of the most popular courses in the department, including a course on Science and Religion that he co-taught with chemistry professor Robert J. Cave and that invariably had a large wait-list. He was a leader among the STS faculty in Claremont, helping to sustain the strong sense of collegiality that has made the 5C STS program such an important part of undergraduate education within the Consortium.

He was also a tireless advocate for diversifying the Harvey Mudd faculty and student body, and for curricular and co-curricular efforts to improve the student experience for students from marginalized groups. “His role in creating an ongoing conversation about diversity and the College’s responsibilities to embrace it can’t be overestimated,” says Jeffrey D. Groves, Louisa and Robert Miller Professor of Humanities and a former dean of the faculty.

Dick’s intellectual style was anything but superficial; he was deeply knowledgeable and always insightful about the subjects that he studied. Yet he maintained a breadth of erudition that is increasingly rare in the academy. “Dick was not just a first-rate researcher, but a true renaissance intellectual,” recalls Paul Steinberg, professor of political science and environmental policy and Malcolm Lewis Chair of Sustainability and Society. “Moreover, he was unfailingly generous with his time and his insights. I could pop into his office on a moment’s notice, soliciting his views on some subject—epistemology, science and society, anything—and he wouldn’t miss a beat. He would drop everything and jump right into the conversation.”

Dick’s ability to foster a sense of intellectual community within the Department won him the love and esteem of successive generations of departmental colleagues. Dean of Faculty Lisa Sullivan, an economic historian, joined the department in 1990 and found his support crucial in her early career: “Among the many gifts that Dick gave me as a colleague and a friend, I find myself most remembering the way in which he made HMC home for me as a fellow historian. It would have been so easy, particularly in my first years at Mudd, to have gone weeks or months without a conversation about scholarly work, but Dick always had an insight he wanted to test out or a manuscript he wanted reviewed. It was a long time before I appreciated that he was intentionally opening the door to reciprocation, making it easy for me to pull up a chair and share what I was working on.”

That sentiment is echoed by colleagues from later cohorts of faculty, including Associate Professor of the History of Science Vivien Hamilton, who now holds the position opened by Dick’s retirement. Hamilton recalls “how much I appreciated that Dick was still around on the hallway my first few years here. His advice and his generosity with his books meant a lot, and now many of his books line my shelves—a lovely continuity of decades of history of science at Mudd.”

These reminiscences remind us that well before—and well after—the department had any formal mentoring in place for junior faculty, Dick had quietly assigned himself the role of mentor, encourager and sounding board. He was a colleague whose extensive knowledge and unending generosity so many of us benefited from. Groves reflects, “Perhaps my favorite thing about Dick was the interest he took in younger colleagues. He was pretty systematic about being in contact with junior colleagues and helping them where he could, and that was a wonderful thing for young faculty members.”

Others in the department agree. “Whatever you were working on,” says Professor of Philosophy Darryl Wright, who joined the department in 1991, “you could benefit from talking with Dick about it. But it wasn’t just that. Dick and his wife, Kathy, were concerned for the wellbeing of junior faculty members just getting acclimated to the College. Some of my happiest memories from my early years at Mudd, during the 1990s, are of Thanksgivings at Dick’s home. He had some noteworthy culinary talents and played a mean game of Trivial Pursuit.”

The abstracted nature of academic life during the pandemic has, in some ways, made Dick’s passing seem not quite real. But we know that will change. Professor of Comparative Literature Isabel Balseiro expresses a sentiment all of us in the department who knew him share: “Dick had a love so deep for this College that even retirement did little to diminish his presence on campus. So when life returns to the College after the pandemic that has kept us all away, I know it will be a very different place without the privilege of seeing him.” It was, indeed, a privilege always.