“Why Do People Justify Oppressive Systems?” by Anup Gampa

February 24, 2021

Wealth inequality in the U.S. is at unprecedented levels, and yet we don’t see the kind of resistance to it that one might expect, especially from the ones who are most hurt by it. Every field of social science has its fair share of theories to help understand resistance to oppressive systems, and so does social psychology. One of the most productive theories in social psychology tackling this question is system justification theory (SJT), which was part of my doctoral research. Here, I’ll share some pieces of that work.

According to system justification theory, people are motivated to see themselves and the groups and systems they belong to as good and just. For instance, random participants assigned to groups based on arbitrary criteria (a coin toss or color of their shirt) will show favoritism in follow-up experiments toward members of their own newly made group and prejudice toward members of the other groups.

For people with higher socio-economic status, it is easier to align judging themselves as good and judging the society they belong to as good because they can perceive their situation as, “I’m doing well because I”m a good person and in this society, good people do well because this is a good society.” This is harder for people with lower socio-economic status. Their narrative might be: “I’m a good person, yet my life is harder relative to others, but this should not be the case if I’m living in a good society. So, either I don’t live in a good society, or I’m not a good person.”

My interest is in understanding the motivations and responses of the dominated members of a society. A growing literature suggests that system justifying attitudes are “sometimes strongest among those who are most harmed by the status quo” (Jost, Banaji, & Nosek, 2004, p. 881). For instance, using a set of U.S.-based national survey studies, Jost et al. (2003), shows that

- low socio-economic status and Black Americans were more likely to endorse limitations on the rights of citizens and media representatives to criticize the government

- low-income Latinxs expressed more trust in U.S. government officials and expressed a stronger belief that “the government is run for the benefit of all” than high-income Latinxs

- low-income respondents were more likely to believe that large differences in pay are necessary to foster motivation and effort than high-income respondents

- low-income participants and Black Americans were more likely to believe that economic inequality is legitimate and necessary.

What might explain this counterintuitive finding? One way to understand these data is in understanding the way that the dominated, i.e. people with lower socio-economic status, might perceive the situation. As mentioned above, the dominated, like everyone else, want to see themselves as good and just and the society they live in as good and just, yet their own situation is worse off relative to others. So, assuming one is most motivated to see oneself as good, this leaves them with the problem of thinking of oneself as good, yet also choosing to stand by and live in an unjust society. This is a cognitive dissonance that one is motivated to overcome.

Justifying a system, then, provides enough psychological benefits and plays a palliative function by “reducing anxiety, guilt, dissonance, discomfort and uncertainty for people who are in positions that are either advantaged or disadvantaged” (Jost & Hunyady, 2003). Thus, the boldest claim of system justification theory is “… that people who are most disadvantaged by the status quo would have the greatest psychological need to reduce ideological dissonance and would, therefore, be most likely to support, defend and justify existing social systems, authorities and outcomes” (emphasis added; Jost et al., 2003, p. 13). As a corollary, SJT also argues that attitudes of system justification strengthens when inequality in the system is made especially salient (Jost et al., 2015).

My work as an activist and organizer provided me with first-hand experiences that contradicted this theory. Even more so is the understanding I gained from studying people’s histories, revolutionary movements across the globe and at “home,” including but not exclusively Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, LGBTQ and the actions and reactions to complexities faced by the oppressed. So, when I came across SJT, the first step I took was to do a deep and wide literature review.

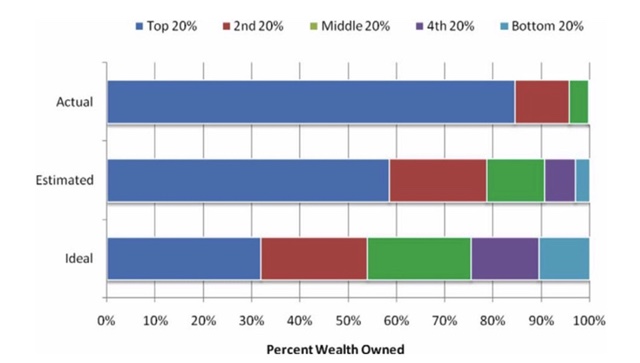

One of the articles I came across was a nationally representative survey by Norton and Ariely (2011) measuring U.S. citizens’ beliefs about wealth inequality in the U.S.—specifically, how much inequality exists and how much is acceptable. There is, in fact, much greater inequality than respondents believe. Similarly, Davidai and Gilovich (2015) demonstrated that U.S. citizens’ understanding of income mobility is inaccurate: people believe there is more upward mobility in the system, and poorer participants especially overestimate the levels of upward mobility.

Interestingly, neither of these papers asked the participants to judge the fairness of the U.S. economic system; they were just asked to estimate the current situation. Building on this line of work, I hypothesized that one reason for a lack of uproar against rising economic inequalities in this country could be due to ignorance about said inequalities.

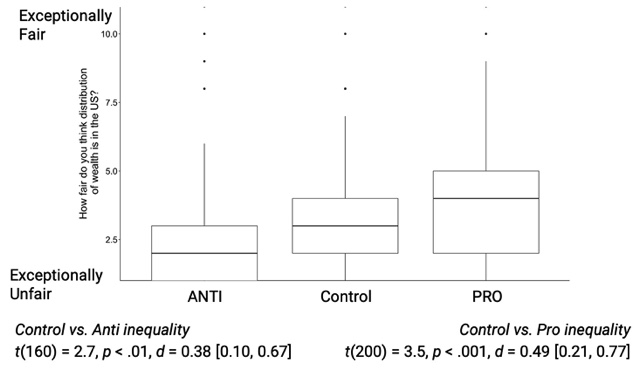

I tested this hypothesis with data collected through experiments and archival data. In an experiment building on the Norton & Ariely (2011) methodology, I first explained to study participants what wealth is. I then asked them to split up the society into quintiles, from the richest 20% to the poorest 20%. Based on these quintiles, they indicated what they considered the ideal wealth distribution in a society and then gave their estimated current wealth distribution (Figure 1). I then split the participants into three groups (“conditions”) distinguished by the information I provided to them: control, anti-inequality and pro-inequality.

In the control condition, participants ranked the fairness of the current wealth distribution on a scale ranging from “Exceptionally Fair” to “Exceptionally Unfair.” For the anti- and pro-inequality conditions, I first provided the actual wealth distribution data for the U.S. I then showed participants in the anti-inequality condition a video discussing why inequality is unfair, while showing participants in the pro-inequality condition a video discussing why inequality is fair. Both groups were then asked to rank the fairness of the current wealth distribution.

So what were the results? In contrast to the findings of system justification theory, participants in general find the U.S. wealth distribution to be unfair. Their judgment is harsher if they are provided with information criticizing wealth inequality and softer if provided with information supporting wealth inequality (Figure 2).

More importantly, in contrast with the argument that the oppressed may be more motivated to justify an unjust system, the oppressed were, in fact, more critical of wealth inequality in the system even though they were simultaneously less-informed about the reality of wealth inequality. Specifically, Black participants and poorer participants underestimated the inequalities in the system compared to White participants and richer participants. Participants with higher family incomes rated inequality in the system as more fair and, though not statistically significant, White participants rated it as more fair when compared to Black participants, and men rated inequality in the U.S. as more fair compared to women.

Overall, across four studies, I show that

- the average U.S. citizen agrees that inequality in the U.S. economy is too high

- one becomes more critical of the inequality when one is presented with information about inequality in the system

- the oppressed are not more willing to justify the inequalities in the system

- the oppressed might be less informed of the inequality in the system—potentially resulting in being less critical, and

- feeling excluded and insecure about future income prospects doesn’t necessarily prevent one from seeking information critical of the system.

The next step in this research is to understand the implications of these studies. Is it the case that wealth inequality at a national level, unlike gender inequality or beliefs in the sanctity of marriage, is a special case in terms of system justification? If so, given the outsized impact of wealth inequality on our lives, do these results diminish the explanatory power of SJT?

Another line of inquiry I’m curious about is the possibility of “compensatory” justification. If one aspect of, or one system you belong to, is criticized, do you satisfy your need to feel good about the systems you live in by overstating how good you believe another part of the system to be? In one experiment, participants who read a passage critical of the nuclear family rated the U.S. as more just (Wakslak, Jost, & Bauer, 2011). In such an experiment, the participant might be left feeling less positive about the nuclear family system, so when asked to judge the U.S. as a system as a whole, rates it as relatively more positive in order to compensate for their judgment of the nuclear family system. Studies like these raise the possibility of “compensatory” justification, i.e., criticism of one system (or an aspect of) could potentially lead to the defending of a different system (or a different aspect of), where the defense of the other system functions as a palliative.

Ultimately, I hope this research will provide a better understanding of the psychological mechanisms at play when considering the attitudes of the oppressed toward oppressive systems. You can try the experiment described above and read the full dissertation. Starting this summer, I plan to finalize the dissertation for publication and start on experiments to study “compensatory” justification. Given that the data presented here was collected in 2017, do these results still hold after the greater discussion on inequality in the U.S. as a result of movements for Black Lives and campaigns by politicians, such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and COVID19? I also plan to teach a psychology of oppression class in Fall 2021.

Please feel free to reach out to me if you are interested in either working with me on the manuscript or want to know more about the class, or both. [email]agampa at hmc.edu.[/email]

Anup Gampa, assistant professor of psychology, focuses on the relationship between an individual’s psychology and the social—particularly social movements, racism and capitalism.

References

Davidai, S., & Gilovich, T. (2015). Building a More Mobile America—One Income Quintile at a Time. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(1), 60–71.

Jost, J. T., Gaucher, D., & Stern, C. (2015). “The world isn’t fair”: A system justification perspective on social stratification and inequality. APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 2: Group Processes., 2(Idc), 317–340.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25, 881–919.

Jost, J., & Hunyady, O. (2003). The psychology of system justification and the palliative function of ideology. European review of social psychology, 13(1), 111-153.

Jost, J.T., Pelham, B.W., Sheldon, O., & Sullivan, B.N. (2003). Social inequality and the reduction of ideological dissonance on behalf of the system: Evidence of enhanced system justification among the disadvantaged. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 13-36.

Kay, A. C., Jost, J. T., & Young, S. (2005). Victim derogation and victim enhancement as alternate routes to system justification. Psychological Science, 16, 240–246. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00810.x

Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2011). Building a Better America—One Wealth Quintile at a Time. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 9–12.

Wakslak, C. J., Jost, J. T., & Bauer, P. (2011). Spreading rationalization: Increased support for large-scale and small-scale social systems following system threat. Social Cognition, 29(3), 288-302.