“Caliphate is ISIS Fan-Fic,” by Ambereen Dadabhoy

March 23, 2021

As a rule, I don’t pay much attention to explicitly Orientalist media. I get enough of it implicitly, through the back-door, as it were, by virtue of being a living, breathing citizen of the United States of America. Our mainstream, political, and popular culture is full of exoticized, eroticized, dangerous, and damaging portrayals of the East, Muslims, and Islam. So when the podcast, Caliphate, was released in April of 2018, I had no interest in subjecting myself to what was sure to be an exercise in western extremist Orientalism. Things changed, however, when The New York Times published a retraction stating that Caliphate did not meet their journalistic standards and that the information they so authoritatively presented in it had not properly been vetted. Then, I binged this podcast and came to see how it gained such popularity and critical accolades (hint: it caters to the white gaze and War on Terror Culture) and understood it to be ISIS fanfic.

The first words spoken by Rukmini Callimachi, “the star terrorism reporter” for The New York Times, “how does ISIS prepare you to kill people,” offers us the Orientalist frame through which she would lead her audience through the psychology and geography of “the Islamic State.” ISIS are killers and they turn people into killers. I am not here to suggest that ISIS was anything other than a disgusting and brutal regime of violence that appropriated Islamic theology, jurisprudence, and sunnah (the way of the Prophet Muhammad) to enact their own murderous agenda. What I am here to expose, however, is the way that this podcast relied on Islamophobic and Orientalist framing in order to peddle lies as truth so that it could sell a narrative that fit and corroborated the creators’ own preconceived notions of Islam and Muslims. Callimachi eagerly ingested the fabrications of her native informant because he was telling her what she already knew to be “true” about ISIS.

She, her team, and the NYT worked harder on making the faulty timeline fit their prescribed narrative (episode six) than they did on vetting their source. They also seem to have overlooked the fact that the point of a native informant is to confirm your preexisting beliefs, which they swallowed wholesale. There’s even more here, however. The larger story of Caliphate isn’t just the need to find evidence that will fit the story you’re selling. It’s the need to make yourself the hero of the story, to be an authority and player in the global War on Terror, and the culture it has spawned.

If you’ve been alive for the past two decades and have taken even a cursory interest in the U.S. War on Terror, instantiated in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on 9/11, then you are perhaps familiar with the tropes and figures that animate and feed the representation of Islam and Muslims that are integral to the public relations arm of the war. For example, the old canards that “Islam is incompatible with modernity;” “Islam needs to have a Reformation;” “Moderate Muslims need to combat extremism;” and “Muslims can’t assimilate to our culture” all position Islam and Muslims as Other, as radically different from U.S. and western values and culture. Going hand in hand with such framing is the continued emphasis on “Islamic violence and terrorism.” This locates any and all acts of violence and terrorism in Islam and Muslims, delegitimizing Islam’s religious standing and authority, while also pathologizing Muslims as violent. These kinds of representations and understandings of Islam and Muslims are a part of what scholar Moustufa Bayoumi calls “War on Terror Culture,” wherein Islam and Muslims are only seen within the narrative of the War on Terror and its prescribed scripts for our religion and our identities.

Caliphate, as both a product of War on Terror Culture and an active propagandist of it, deeply relies on the apparent truth of the tropes that the War on Terror have created for Islam and Muslims. It goes even further, however, by being ISIS fanfiction (fanfic). For those unfamiliar with fanfic, it is the writing of “stories produced by fans on plot lines and characters from either a single source text or else a “canon” of works; these fan-created narratives often take the pre-existing storyworld in a new, sometimes bizarre, direction” (Bronwen Thomas). Fanfic empowers fans to enter their favorite canons and to play with the characters, plots, scripts of those universes. Fanfic is a particularly apt descriptor for Caliphate (if I do say so myself) not only because of the fictional narrative of “Abu Huzaifa” that is supporting the whole enterprise, but also because Callimachi, like many fanfic writers, seeks to enter the canon and position herself as an authority, victim, and savior within the terrorist plot. Callimachi is an expert in the western canon about ISIS, she is an on-the-ground reporter on the terrorism beat, having covered “Islamic extremism” for the AP and NYT. Within the parameters of this podcast, however, she seems to have been freed from some of the more stringent demands of accuracy necessary in news reporting (although we come to find out that several of her newspaper stories needed corrections, too). Caliphate is ISIS fanfic because it literally has a story to tell, one that is constructed for the author to legitimize her beliefs and knowledge, one that is not borne out by the truth.

In Caliphate, Callimachi becomes an Original Character, which, in fanfic terms, is an authorial intervention within the canon, sometimes an avatar of the author themselves to become the love interest of the canonical protagonist and other times to take the place of those protagonists. We get a sense of this early on in the series, in episode two which is conveniently called “The Reporter.” Callimachi’s heroic credentials are established through audio clips and soundbites of her in “the war zone,” as we hear sounds of gunfire and bombs and learn that she’s on the ground, rooting through the rubble, collecting the valuable information that will be needed to win the battle against this dangerous enemy. (I’m wondering here about the ethics of grabbing evidence and taking it away before the authorities can collect and review it. Is this how journalism works?) The episode rehearses the ease with which she was able to find and interview her informant (maybe that should have been the first clue that this was a fraud?) and also her own personal experience of being targeted by ISIS. We hear about her being contacted by the FBI and told that she’s the subject of a threat from “the Islamic State.” This meeting leads to her fearing one night (about a year later) that ISIS is literally outside her home. What actually happened is that there was a water main break on her street and the water department was knocking on doors to notify residents. What happened in the reporter’s head was the fear that ISIS was going to attack her, and so she called 911, letting them know that she’d been targeted by ISIS and that the FBI has told her that she was “on a list.” This narrative exposes the paranoia and fear that ISIS generated in many people during the time that they were active. I’m sure that learning from the FBI that there was a credible threat being made against you by such an organization would be terrifying. At the same time, we also see Callimachi placing herself within the broader narrative as a helpless and terrified victim, as someone inside the story now.

As the female protagonist, Callimachi’s interactions with “Abu Huzaifa,” and her discoveries on the ground in Mosul take on new meaning. She’s not only trying to gather new information on ISIS so that we can understand “who we are really fighting,” but she’s now an integral part of the resistance against ISIS and one of the people they are trying to destroy. In episode eight, after the U.S.-led coalition of forces retake the city of Mosul from ISIS, she and her crew are combing through the ISIS offices, and she is utterly gleeful at the discovery of a briefcase and documents, “I’m feeling really excited. I’m feeling, like, giddy, you know?,” and follows up by noting that this work is like being on “CSI ISIS.” The reference to the popular American television police procedural links the War on Terror to U.S. domestic policing, and again it places her in the position of the prototypical heroic “good-guy.” Importantly, she notes “You know, when I’m holding these documents, the thing that’s never far from my mind is that if we hadn’t retrieved these very papers from the rubble, they very likely would have been destroyed and would have been lost forever.” Her words reinforce the importance of her work, preserving these documents from the annihilation or suppression that would be sure to follow, but also cements her importance in the narrative. She has saved these documents. She has preserved history. She is making it possible for us to have the knowledge about ISIS that we need so that we can defeat them.

Callimachi represents the free and fierce womanhood that ISIS, Al Qaeda, and the Taliban have sought to oppress and her positioning echoes Laura Bush’s 2001 comments that “the fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women.” Nowhere is this made more clear than in episode nine, where she tackles the various forms of violence visited upon people in the territories that ISIS controlled. Several things happen in this episode that continue to buttress Callimachi’s heroism and defiance. One of the first instances of western “girl power” we see is a common Orientalist trope, her necessary and symbolic unveiling. She’s attempting to interview a prisoner but the guards won’t let him sit because he’s dirty and has rashes and scabs on his arms. Callimachi, offers her hijab to cover the couch so that the man can be comfortable: “I basically took my hijab, which I had brought on this trip to, you know, to cover myself and to try to blend in, and I asked the commander, could we put my hijab down on the couch, and he can then sit on that.” Orientalist media make much of non-Muslim women reporters having to wear a cursory hijab when they are reporting from Muslim majority countries. Rather than a sign of respect for those cultures, the hijab becomes a symbol of women’s oppression and cultural misogyny. Scenes of unveiling, like this one, then, have a special frisson: they violate and transgress cultural norms and free these brave women from the tyranny of Islamic misogyny. As in other popular media where we see such scenes—I’m looking at you, Grey’s Anatomy and 9-1-1 Lonestar—there is no intelligible reason for this unveiling, and yet we cannot have our Orientalist propaganda infotainment without it.

Caliphate must also confront the use of sexual violence by ISIS. For the podcast, these acts reinforce the inhuman brutality of the regime and its followers. What the podcast doesn’t make clear, however, is that the rapes committed by these men violate the principles of Islam, thereby exposing the hypocrisy of their claims to any kind of Islamic state. Regardless of this fact, the show must proceed according to its own logics, which tie in very neatly to those of the War on Terror, again perfectly encapsulated by Laura Bush: “Civilized people throughout the world are speaking out in horror, not only because our hearts break for the women and children in Afghanistan but also because, in Afghanistan, we see the world the terrorists would like to impose on the rest of us.” While she was addressing the nation in 2001, only a few months into the U.S.’s invasion of Afghanistan, her comments remain applicable to any and every front in the War on Terror. Caliphate offers us the evidence of victimized women and children, particularly their sexual abuse at the hands of ISIS members. When she encounters a prisoner lying about the “female sex slaves” he owned, Callimachi seeks to recuperate the stories of Yazidi girls brutally victimized by these men.

Using her contacts, she finds the young woman the prisoner claims to have helped, and gets the survivor to relate the story of her trafficking and abuse by these men. This is an attempt at justice, but we don’t know for whom that justice is being performed. We have not been offered any evidence for Callimachi’s training to talk to these young girls and women, nor do we know what kind of psychological damage she might be inflicting upon them by asking them to go over what happened to them. We also remain ignorant as to the psychological help she might have offered them after forcing them to relive their trauma. The cause, knowledge and exposure, is framed as noble, and so these questions are not raised. We are meant to believe that if not for Callimachi, this young woman would not have closure, again these are Callimachi’s words, not the words of the survivor, “But the fact is, this young girl wouldn’t have even known that he was in jail if it weren’t for this accident of journalism, if it weren’t for the fact that a group of New York Times journalists just happened to walk into this prison on this particular day.” So, the story of this brutality and the bravery of the young woman is turned into a white savior narrative, where Callimachi in service of the War on Terror finds justice for this young woman and also ensures the protection of “the rest of us.”

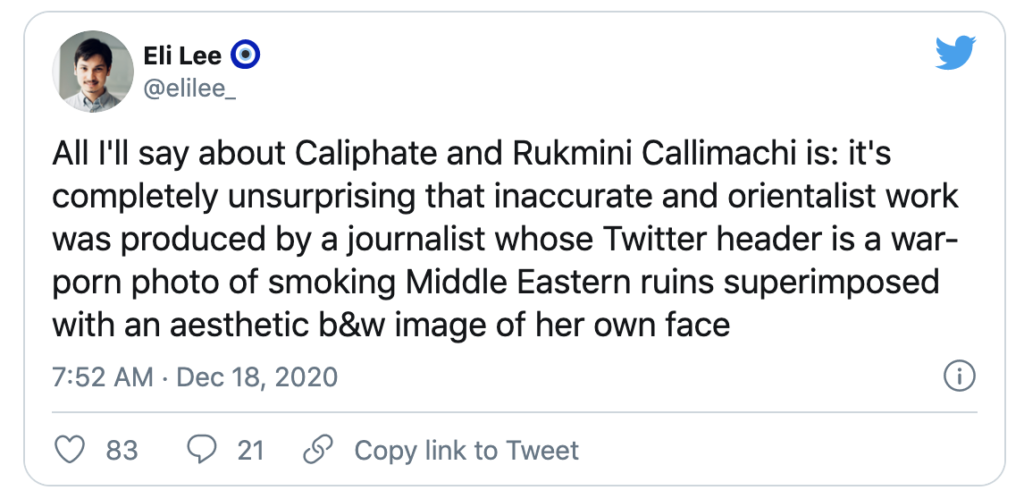

Perhaps the best evidence of Caliphate‘s fanfic foundation is the podcast’s cover image. As Eli Lee points out in this tweet, the juxtaposition of a bombed city with half of Callimachi’s face highlights the role of the heroic persona cast for her within the narrative that she has written, which is ostensibly about ISIS.

It is Orientalist in its depiction of the geography as violent, arid, and lifeless and in its contrasting positioning of white womanhood. The relation, which the division suggests is equal, is swiftly revealed to be unequal when we begin listening. Callimachi is the authority here, and her voice guides and overrides all others. Moreover, the role of white womanhood and its imperial gaze, particularly in the context of Islamicate societies cannot be overlooked. Here we have white womanhood not only as the authority, but also as tacitly approving the “war-porn” nature of the geography over which she has power. The Orientalism upon which Caliphate is built is a fantasy. It is as much fanfic as this podcast. Unfortunately, the regimes that put such Orientalism to use have material power, which they can and do exert with the help of accomplices like Callimachi. Indeed, this podcast makes transparent the academic-military-complex that Edward Said signaled in Orientalism and to which he added journalism in Covering Islam. These institutional entities have the power to shape and frame our knowledge and understanding, and yet when they themselves are steeped in Orientalism, their truth claims only corroborate and substantiate what they think they already know. Thus, we arrive at Orientalism’s citationality and that of the podcast. Over and over again, we are told that the informant’s statements are in line with Callimachi’s knowledge. The lining up on the evidence within the Orientalist framework proves its truth. Orientalism authors and authorizes itself.

There remains much more to say about Caliphate and the unethical standards of journalism that allowed it to be published, broadcast, and collect media accolades. Not only did Callimachi and her creative partner win a Peabody award for the series, but also they were Pulitzer finalists. The acclaim highlights the rewards that peddling in War on Terror media yields. It further exposes the complicity of elite institutions of power and prestige to grant their imprimatur’s on narratives that fit their tidy readings of Islam. Narratives that are, in other words, Islamophobic and cater to the white gaze. Having these trophies rescinded or returning them in light of the deficits in the podcast’s veracity is not enough, and one hopes that moving forward such awarding bodies will be more reflective in their need to satisfy their own Orientalist and Islamophobic desires.

I am not here in any way offering an apologia for ISIS. That I have to make this clear, is of course, a demand made by Islamophobia, which colors all Muslims as potentially complicit in the violence perpetrated by people who claim religious affiliation with us and who seek to speak for all 1.7 billion of us. What I am taking issue with is the uncritical positioning of ISIS as having any kind of legitimacy within the Islamic community which is vast, multiethnic, multicultural, multilinguistic, multiracial, and multinational. By all measures Muslims across the globe have disclaimed this fringe group; however, by referring to them even as Islamic extremists, the propagandists of War on Terror Culture continue to define what and who Islam and Muslims are. Caliphate falls in line with such constructions.

This article was first published December 23, 2020 on the blog of Ambereen Dadabhoy, associate professor of literature at Harvey Mudd College. Her teaching and research pursues lines of inquiry directed at uncovering culturally fraught representations of difference, which include gender, race, and religion. She offers courses in Shakespeare and early modern English literature, freshman writing seminars, and genre electives.